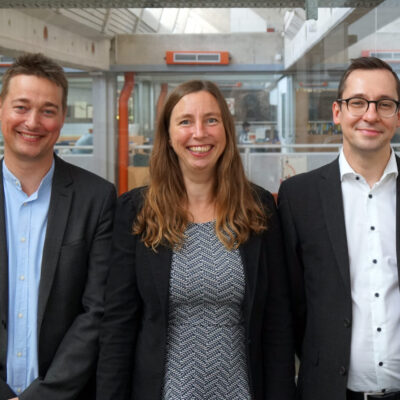

Philosopher Nancy Cartwright is investigating the role of theories in science. She is one of the two keynote speakers at the anniversary conference on 15 November – and has agreed to answer a few questions in advance.

Professor Cartwright, have the great theories become outdated? This is one of the questions being raised at Bielefeld University’s anniversary conference.

Nancy Cartwright: I don’t think so. But that depends on what you expect of them. They do not, and never have, laid down fundamental truths about nature and society. They serve, I believe, rather, as general frameworks within which to think, frameworks that provide us with strong positive heuristics and with constraints, with sets of tools, ideas and principles for developing concrete theories and models that then can be used to describe, explain, and predict what happens in the empirical world. Think of the importance of the whole framework of general theory of relativity for the study of gravity waves; or of how Judith Butler’s framework of gender as performativity transformed studies in gender and queer scholarship.

What alternative possibilities does science have to meet the challenges of our time?

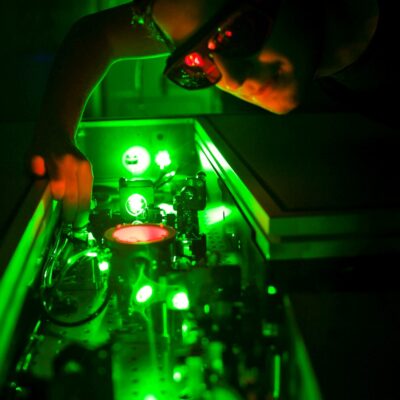

Nancy Cartwright: For problems where grand general theories offer us no leads, we can go for middle-level theories directly—theories that make no claim to wide generality. These are the familiar theories we use all the time to get around in the world, theories that are local, ceteris paribus, subject-specific, often using concepts, measures, techniques, and methodologies specific to the problem area or subject matter, like the theory of the laser or of the democratic peace.

With or without the guidance of grand theory recommending where and where not to go and broad indicators of how to get there, we have to get down to the nitty-gritty details, getting on with the tasks of everyday science. There are no big sweeping answers, but lots of small hard tasks, many of which will accomplish little that holds over great sweeps of nature or society but without which solutions will not be found.

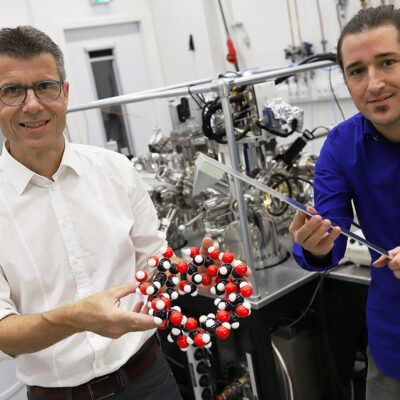

Bielefeld University has been committed to interdisciplinary research since its foundation. What can interdisciplinarity achieve when it comes to theories?

Nancy Cartwright: I have mostly been involved not with theory testing or development but with the use of theory. This inevitably calls for a host of disciplines. No problems in the real world lie snugly within any single theoretical domain, nor usually even in a handful.

I first cottoned on to this when I was working at Stanford as a philosopher of physics with a love of quantum theory. I wanted to learn in detail how it was put to use, for instance in designing lasers. It turns out I couldn’t do this in the physics department; I had to go to the engineering department. And there I found I knew virtually nothing already that could help in understanding lasers.

Now I look at theories for social interventions, like the use of mobile phones with special apps to improve childhood nutrition. There is a middle-level theory about how this intervention is supposed to work: use of the apps is supposed to produce better calculation of each child’s status, which is supposed eventually to result in better recognition of the scale of childhood nutrition problems and pressure for government action. This is a long causal chain, and understanding why and whether it will work at each step requires bringing together a wide range of cross disciplinary and local knowledge and techniques. There is no avoiding the need for true interdisciplinary cooperation if we want good real-world outcomes.

Professor Nancy Cartwright from the University of California in San Diego (USA) and Durham University (Great Britain) is one of today’s leading researchers in the field of theory of science. For many years, she concentrated on philosophical aspects of physics and economics; nowadays, her research focuses particularly on evidence-based policymaking. She is one of the two keynote speakers at the anniversary conference ‘The Theoretical University in the Data Age’. Her talk on ‘Why Big Theories are Here to Stay’ will start at 9.15 a.m. on 15 November. Scientists willing to participate in the conference can register here.

This article is a pre-publication from BI.research, the research magazine of Bielefeld University. The new issue of the magazine will be published in November 2019.